The wine roads of Bordeaux

A chef of a Michelin starred restaurant in Bordeaux once said, ‘All French culture can be seen on the table’. Wine is an integral part of the typical French meal. Bordeaux is one of the few wine regions in the world that gives a wine connoisseur such a broad range of exclusive wines with different characters, styles and colours. Bordeaux produces red, white, dry, sweet and rosé wines as well as cremants. The chateaux Margaux, Lafite, Mouton Rothschild, Latour, O-Brion, Yquem, Petrus, Le Pen, Ozone, and Cheval Blanc are the most expensive wines in the world, and they are produced in Bordeaux.

In this region, it is difficult not to love wine, because life seems to be all about it. Whatever the weather, come rain or shine, all talk revolves around how this will affect future harvests. Yet this isn’t surprising, because Bordeaux is the largest vineyard area in France and the world leader in the production of origin-controlled (AOC) vintage wines. Every sixth person in the region, directly or indirectly, is involved in winemaking. At the negotiating table and in a restaurant, on holiday and at the workplace, sooner or later people will begin to talk about wine and food.

There is no record of when the first vineyard was cultivated in Bordeaux. However, in the 1st century AD, vineyards covered the whole province of Aquitaine. There were so many of them that in 92 AD the Emperor Domitian had not only to impose a ban on further planting, but also to order the reduction to as much as half of the existing ones. The Act was repealed only in the 3rd century by the Emperor Probus.

There have been several golden ages in the history of winemaking in Bordeaux. In the 13th century, the port La Rochelle, the largest vineyard in Aquitaine, surrendered to the French Crown, and English kings had to buy wine in Bordeaux. At that time the port of Bordeaux amassed wines from Bergerac, Cahors, Gaillac and Pamiers. However, this did not last long, and in the middle of the 13th century, Bordeaux got the right from English kings to be the first in selling wines from the banks of the Garonne. At that time no one knew how to stabilize wine, and it gradually turned to vinegar. Therefore, the privilege of priority sales was very important; while wine from the neighbouring regions became vinegar, the merchants from Bordeaux had already had a chance to sell theirs and even to collect the revenue.

In the 17th – 18th centuries, drainage work was carried out in Médoc, which turned wetlands into areas suitable for winemaking. The Bordeaux members of parliament began to buy these areas for vineyards, and this is how the chateaux wines of Médoc appeared.

In the 21st century, the Asian market decided that it was prestigious to drink Bordeaux, and the Grand Cru prices rose to unprecedented levels. In good years, Lafite, Margaux, Pétrus, Ausone and others cost several thousands euros. Fortunately, for ordinary wine lovers Bordeaux offers lesser known, but very good wines.

There is a saying in Bordeaux that goes ‘In a good year, buy the small chateaux wines and in a bad year, the grand chateaux ones!’

‘To be beautiful a vine should suffer!’ The sadistic approach to winemaking brings many benefits. A vine’s suffering begins in its infancy. First, it is grafted upon the roots of an American vine. This is a prerequisite which was introduced in the late 19th century to combat the vine pest phylloxera, imported from the U.S. The root larvae of the parasite used to attach themselves to the roots of the vines that were not engrafted and killed them within three years. The next stage in the vine’s ordeal is planting. In some areas, the frequency of planting reaches ten thousand vines per hectare. Why? In order to promote competition among the vines and ‘let the best vine win!’ Lastly, it is forbidden to irrigate vineyards, because it is required that the vine search for moisture and nutrients deep in the soil without any assistance.

The Wine Rivers of Bordeaux

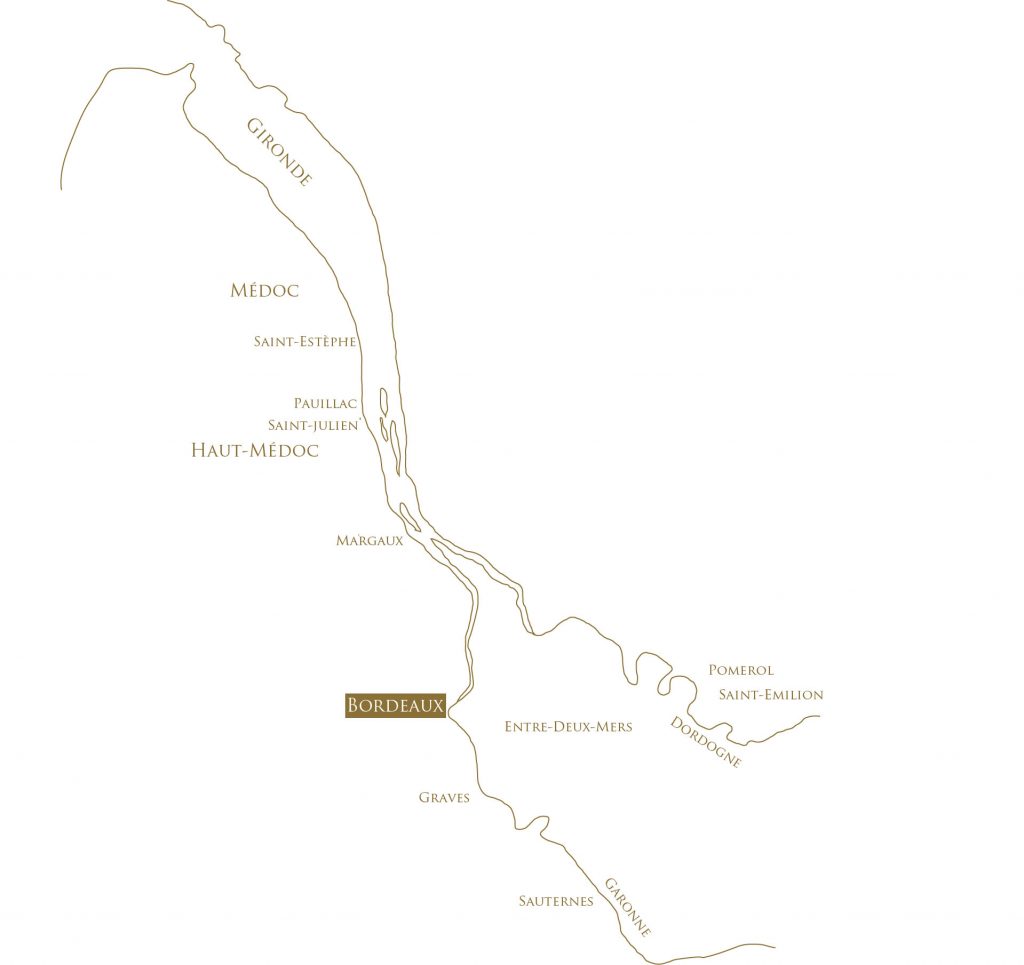

When one starts talking about Bordeaux, the image of thick dark red wine immediately comes to mind. This comes as no surprise because the name of the claret red colour, which until the middle of the 20th century was called the ‘bordeaux’ colour, derives from the colour of Bordeaux red wines. Some connoisseurs call Bordeaux wines ‘the wines of the rivers’, because the borders of winemaking regions are traced by the flowing watercolour lines of the three major rivers: the Dordogne, Garonne and Gironde.

On the left bank of the Garonne and Gironde there are the vineyards of Médoc, Graves and Sauternes. Between the Garonne and the Dordogne there is a winemaking region called Entre-deux-Mers – ‘Between two seas’. On the right bank of the Dordogne lie the St. Emilion and Pomerol vineyards. These are the most famous winemaking regions in Bordeaux. Overall, there are more than 57 appellations that are detailed in wine encyclopaedias.

The Alchemy of Wine

Oenologists point out that the unique quality of Bordeaux wines is determined by four major factors. First, the mild climate and the structure of soil (terroir); secondly, the kinds of grapes used in winemaking; thirdly, yearly weather conditions (millésime); and fourthly, the knowledge and experience of winemakers. The climate of the region is influenced by the proximity of the ocean. Winters are warm, and periods of snow are rare and short-lived. There are exceptions, of course, that once again confirm the rule. January 2007 was marked by a snowy week that brought lots of fun to children and lots of worry to winemakers.

Bordeaux produces mainly blended wines that are a combination of wines of different grape varieties. The established norms allow the planting of only twelve types of grape – six red wine grapes and six white – in the province. The most common reds are Merlot, Cabernet Sauvignon and Cabernet Franc, while the most common whites are Semillon, Sauvignon and Muscadelle.

The whites ripen slightly earlier than the reds, so their harvest begins in August or September. For this period, every winery hires seasonal workers, and the grapes are gathered by hand. For white wine, grape clusters are squeezed in the winepress, the juice is poured into large vats or barrels. The next steps include alcoholic fermentation and aging in oak barrels during 8-12 months. However, aging in barrels is not mandatory, and many wineries do not do this.

The red wine making process is different from the production of white wines. After being harvested, the grapes are transported to the winery and sorted on the sorting tables. the grape is crushed (the crushing consists of breaking the grape berries to extract the must without crushing the seeds). Next, a mixture of grape juice, skins, pulp and seeds is poured into large vats. At this stage, different grape varieties are not mixed.

Alcoholic fermentation takes about 7 to 10 days. During this time it is necessary to control the temperature in the vat so that it does not rise above 32°C, otherwise the yeast, which converts sugar into ethanol, will die. The fermentation process releases carbon dioxide, which pushes the grape skins, pulp and seeds up to the surface, forming a so-called ‘cap’.

Grape juice has no colour, as all fragrances, colour and tannins are in the skin and seeds. To extract these elements a winemaker makes a mixture of the must and the cap, which is followed by maceration. The flavoured bordeaux must is separated from the grape skins, pulp and seeds, then further fermentation takes place. After this, wine is transferred to oak barrels where it ages from 8 to 24 months. During all this time, the wine evaporates through the pores of the oak, so the winemaker must constantly refill it to avoid the wine turning into vinegar.

Barrels – but not for honey

Particular attention is given to the choice of oak barrels. The first important thing is the wood used. The barrels are made from oak, usually sourced in France, Eastern Europe or America. However, most winemakers prefer French oak, even despite the fact that barrels made from American oak are 30 – 40% cheaper than their French counterparts. Among French breeds preference is given to sessile oak wood because of its soft and subtle tannins. The average age of the oak is 150 to 200 years old. The oldest used was from Versailles, from an oak planted in 1680; Marie Antoinette herself would often sit in the shadow of its branches. Tragically, in 2003, the oak could not bear the terrible summer heat, and had to be cut down. The wood was sold at auction and used for making wine barrels. The cost of such a barrel reached 1,500 euros, in lieu of the usual 600 to 700 euros. The volume of a Bordeaux barrel is 225 litres, which fills 300 standard bottles, while the volume of a Burgundian one is 228 litres.

After the tree has been cut down it is split, and the oak staves are left in the open air for two or three years, and sometimes for as long as six years. During this period, the wood dries out in natural conditions. Its exposure to the sun and the rain causes it to lose its colour and tannins, and its humidity is reduced from 80% to 15-18%. It is only after this process that the blackened and strengthened staves fall into the hands of a cooper. He shaves, hoops and warms them in the fire, moistens the wood, making it more flexible, and then shapes them. But that’s not all; for wine, one of the determining factors is the degree of firing. The cooper puts a half finished barrel without a bottom or a top on the fire and burns its inner walls. With a weak firing the barrel gives a vanilla flavour to wine and with a strong firing it imbues the wine with notes of roasted coffee, caramel and smoke.

Vineyards give abundant information about winemaking in Bordeaux to the visitors, so we won’t dwell on the details any longer; it is time to set off along the wine roads of Bordeaux. It is impossible to visit all the wine regions of the province in a week, but it is a must to visit the most famous ones. So let Médoc be our first destination.